Japan has a very long tradition of stamping seals in vermilion ink on important documents. I believe it was originally imported from China, as with so much else of Japanese culture, but it has taken on a life of its own here. Almost all adults have a personal seal, often more than one, which is stamped, in vermilion, on such documents as marriage papers, or contracts to buy a house.

A “goshuin”, however, is more significant than that. These days, it refers to a large one received at a Buddhist temple or Shinto jinja. The custom appears to be originally Buddhist, and one explanation I have heard is that you take your collection to show to Lord Enma, the judge of the dead, and they serve as visas in your passport, allowing you to pass through hell quickly. These days, however, there does not appear to be a fixed religious meaning for them.

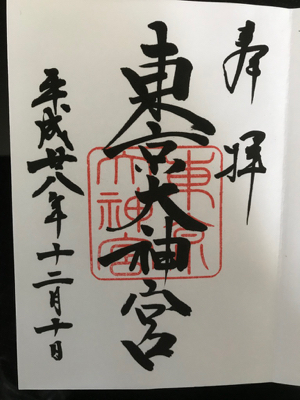

The picture is of a goshuin from Tokyo Daijingū, and is fairly typical. The vermilion seal is normally square with rounded corners, and in the middle of the paper. The characters on the seal are most often the name of the jinja, but not always. The name of the jinja is then written in black over the top. The characters in the top right normally say “veneration offered (奉拝)”, and the date is written on the left. Some jinja have more stamps, of the jinja’s badge, or referring to particular aspects of that jinja’s practice, and others write different things, such as “kami of water” or “sacred island”, that are appropriate to that jinja. At some jinja, where the priests are not confident of their handwriting, the writing is also applied with a stamp. Most jinja ask ¥300 for a goshuin, although some ask more.

The picture is of a goshuin from Tokyo Daijingū, and is fairly typical. The vermilion seal is normally square with rounded corners, and in the middle of the paper. The characters on the seal are most often the name of the jinja, but not always. The name of the jinja is then written in black over the top. The characters in the top right normally say “veneration offered (奉拝)”, and the date is written on the left. Some jinja have more stamps, of the jinja’s badge, or referring to particular aspects of that jinja’s practice, and others write different things, such as “kami of water” or “sacred island”, that are appropriate to that jinja. At some jinja, where the priests are not confident of their handwriting, the writing is also applied with a stamp. Most jinja ask ¥300 for a goshuin, although some ask more.

As indicated by the “veneration offered” characters, a goshuin is supposed to be a record of a visit to a jinja, so you should pay your respects to the kami first, and you should not have other people get them for you. This is in contrast to o-mamori and o-fuda, which may be received for other people and then taken to them. Priests often complain about people who fail to respect these requirements, although normally not to their faces.

The immediate motivation for this post is that my daughter has decided that she wants to collect goshuin, so we bought her a special book (a goshuinchō) for them at the weekend, and today we went to Shirahata Hachiman Daijin to get her first one. She took her friend from school along with us, as well.

In some ways, that is a fairly standard pattern. Recently, goshuin have become very popular, particularly with young women (albeit not generally quite that young). A couple of things really brought this home to me. First, when we went to look for a goshuinchō, we went to a specialist Japanese paper shop first, but it was a small shop, and only had about half a dozen varieties. We then went to a standard stationer’s, and they had a whole island shelf of them, easily thirty varieties, right in front of the doors. When I started collecting them, about ten years ago, the only place I could find a proper goshuinchō was a jinja.

The second thing was that I also got a goshuin from Shirahata Hachiman Daijin today. I had not previously received one, because when I asked ten years ago, they did not do them. My guess is that so many people asked for them that they felt they had to start.

For the religious element, would possession of more goshuin in one’s goshuinchō mean swifter passage through Hell? And did that mean everyone passed through Hell, but those who had visited more jinja in this world were spared from more time in Hell?

Are there more sources we can read about goshuin?

The afterlife beliefs are more Buddhist than Shinto, and I’m not sure of the details. However, I think that’s the general idea; if you don’t achieve enlightenment before you die, you go through hell, but the merits of various temples you visited in life can make your visit shorter. In so far as Shinto has beliefs about the afterlife, they are different.

I’m afraid I’m not aware of any detailed sources on goshuin in English. There are books in Japanese, obviously, but I haven’t read any of them yet.